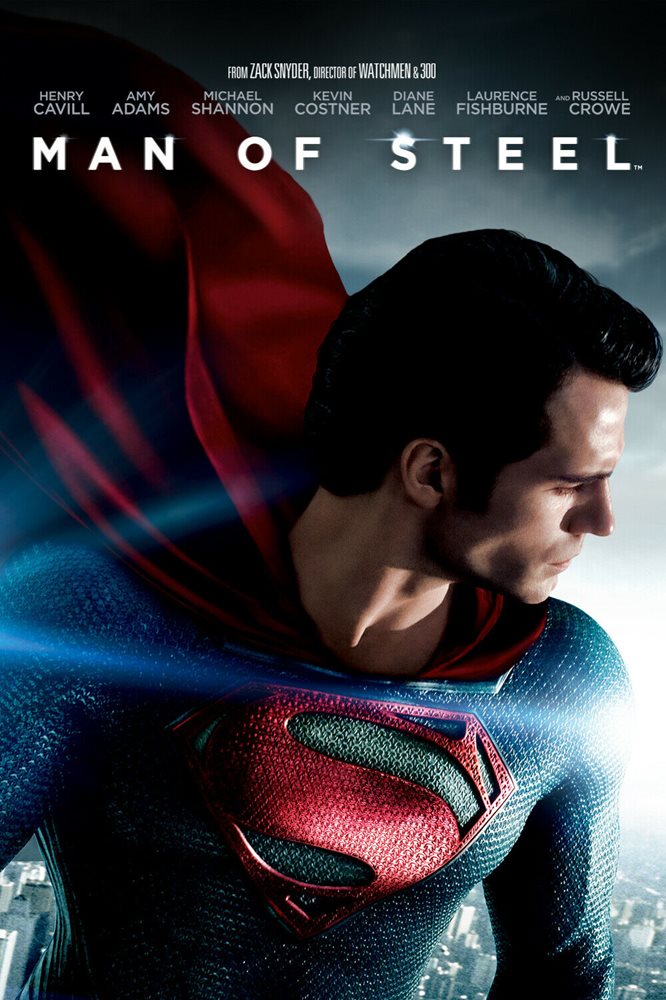

14 Jun Man Of Steel Analysis

MAN OF STEEL

Introduction

I’ll share some relevant background to establish a framework so you can understand my approach to CBMs:

- Growing up I read about 4 comic books (my beloved Mom, with a Masters in English and an accomplished poet herself, HATED them and considered them devoid of value). One was about Smokey the Bear.

- As a kid, despite not having comic books, I basically knew Superman and Batman. Christopher Reeves’ movies (Superman: The Movie and Superman II) were amazing to me, while I’ve always thought the 60’s Batman show was dumb—I didn’t appreciate Batman until…well, 1989’s Batman.

- As an adult, I’ve read a few more comic books/graphic novels, and love superhero movies of all types, filling a void from my childhood with reckless abandon.

- I am agnostic in my preference for DC or Marvel (or any other CBM). I do believe each company has fundamentally different approaches to their superheroes, but I see great value in both.

I present these to show that while I love CBMs, I am generally unfamiliar with specific comic books (which tempers my personal expectations) and may have a bias towards Superman by virtue of not really knowing many other superheroes growing up.

Now, here are a few relevant observations about CBMs in 2013, when Man of Steel was released.

It is generally accepted that the Marvel Cinematic Universe is the absolute peak of comic book movies, and I heartily agree—the Infinity Saga is remarkable as a coherent franchise of 23 films that tell an overarching story. Although in 2013, Man of Steel, Iron Man 3 and Thor: The Dark World came out, and I think most agree that MoS was the best. But it was also in the aftermath of The Avengers, which kicked the MCU into overdrive.

It’s also generally accepted that the DC Extended Universe, which MoS kicked off, has been less accepted by critics and audiences. In my opinion, there are two reasons for this. First, MoS was a pretty radical departure in tone and intensity from all previous iterations of Superman, especially the most recent ones (TV’s Smallville and Lois & Clark, I believe), and audiences were divided in their willingness to accept these changes. And second, I think the MCU trained general audiences to have specific, trained expectations of CBMs due to their very consistent patterns of storytelling, look, quality, etc. These patterns made for fantastic movies, but I think that a majority of audiences began to believe that any CBM that deviated from the MCU’s familiar aesthetic were lesser. This is remarkable because so many people developed such identical expectations (consciously or subconsciously), that any CBM that was non-MCU suffered, even the Fox X-Men films.

Lastly, I also think that Christopher Nolan’s Dark Knight trilogy are the best trilogy of superhero movies yet, and The Dark Knight is my personal favorite CBM. But the problem with the Dark Knight films is that they were rooted in a realism that essentially excluded any other DC superhero from the same universe, and Nolan declined to allow his iteration of Batman to continue cinematically. This left DC in a massive bind: they had some of the best and most profitable superhero movies of all time, but they were forced to reboot their entire universe just as Marvel was hitting its stride.

All of these factors, in my opinion, amounted to a stacked deck against any Superman movie.

2013 and the Attempted Rise of the Cinematic Universe

In the aftermath of the Dark Knight trilogy, which ended in 2012, DC Films was looking to reboot its superheroes as a cinematic universe a la the MCU; in fact, every studio started planning out a cinematic universe, watching the MCU’s financial and critical juggernaut and feeling like they could do the same. Sadly, nobody else, DC included, was willing to put in the work to build a cinematic universe in the same way that Marvel had done starting with 2008’s Iron Man. The MCU had two important secret ingredients: Kevin Feige served as the singular overseer of the entire MCU creative direction, and they had a general idea of overarching stories the MCU would tell.

Paramount tried the same thing with Transformers, and Universal attempted with their Dark Universe. And while the Transformers movies were box office hits, they are incoherent tech demoes of noise and visual effects in the hands of master chaotician Michael Bay; and Universal’s Dracula Untold and The Mummy were mediocre-to-wretched interpretations of monsters that felt like the products of committees of non-creative executive. Both studios failed to tell interesting enough stories or establish any kind of cinematic universe.

The only remotely successful attempt to establish a non-MCU cinematic universe was, in fact, DC. And their greatest failing was not committing to the venture the way that Marvel had done. DC Films is owned by Warner Brothers, which is a movie studio known for giving its filmmakers tremendous creative control…if their films are critical and financial successes. And therein lies the rub, because creative control was not a feature of the MCU at the time; Marvel hired directors that were willing to adapt to the MCU pipeline, which strictly dictated certain aspects of the films they made, including story elements, tone and content, and visual style. Taking these aspects of filmmaking away from filmmakers meant that Marvel struggled to retain truly top-tier directors (Edgar Wright famously left Ant-Man, as did other great directors who were unwilling to let the studio dictate so much of the process). Although Marvel has loosened up to some degree (Taika Waititi!!), in 2013 Marvel and WB had fundamentally different approaches to the latitude granted filmmakers.

Christopher Nolan stands as WB’s greatest creative partner, especially with his Dark Knight films. But Nolan wasn’t interested in continuing with superhero movies—his talents and interests extended far afield, and WB has indulged him ever since (well, until COVID-19 and Tenet…) But Nolan and WB did agree that Zack Snyder was exactly the kind of filmmaker they wanted to kick off their DC cinematic universe.

Director Zack Snyder had an impressive film career up to 2013: his first film, a Dawn of the Dead remake, hit the cultural sweet spot for zombie movies in 2004. He followed it up with 2006’s 300, an visually stunning action movie that happened to be a very precise adaptation of the graphic novel and made a ton of $$$. With two critical and financial successes under his belt, WB gave Snyder the opportunity and budget to make Watchmen in 2009. While flawed, it not only grew in popularity with time, but is a skilled adaptation of a comic that was considered impossible to adapt. Then he made 2011’s Sucker Punch, which was his first truly original film, but a hot mess of incredible visuals, terrible storytelling, and wildly vacillating tones. It was also a critical and financial misfire.

But the trend here seemed clear: when adapting previously existing properties, Snyder was ahead of his time, with a visual style that was universally praised. All of which led to his selection by WB, DC, and Nolan to direct Man of Steel, their equivalent to the MCU’s Iron Man; meant to kick off the DC Extended Universe of films with the greatest superhero of all: Superman.

That’s enough about some of the meta-circumstances that surrounded Man of Steel.

What about the movie itself?

The Movie Itself

Zack Snyder kicked into high gear, with the creative control WB typically granted successful filmmakers, and a mandate to kick off the DCEU. Man of Steel was the first of (at least) five films Snyder wanted to tell an overarching story about Superman. And right away, we hit the first major problem with the DCEU. In my opinion, DC and Snyder failed to convey to the public the scope of what was planned. I understand the need for secrecy, but I think they should have made it public knowledge up front that Snyder had a five-movie plan that would encompass multiple DC superheroes, facilitate spin-offs of these heroes, and would probably be a compressed version of what the MCU was doing.

Instead, secrecy was rampant, and with only one director overseeing their strategy, it would be years between films, not months, as the MCU was doing. Feige was a studio-level creative head, not directly involved in the day-to-day making of the MCU’s films. Snyder was being asked to oversee the DCEU strategy, but also make the movies in the most stressful, busy capacity there is: director. Nevertheless, Snyder did what any sane person would do and made the Superman movie he always wanted.

Zack Snyder’s Man of Steel presents a layered and carefully constructed mythology of Superman that essentially incorporates all of the classical elements of the Superman story but filters them through Snyder’s vision and style. What does that mean? That there is far more thought put into previously glossed over elements of the story, and per his previous films, the style was most definitely ‘dark and gritty’, which post-Dark Knight was a mandate for many CBMs.

The best example is the opening sequence on Krypton, where Superman’s biological parents, Jor-El and Lara, make the horrible decision to send their son, Kal-El, into the void of space. That is the familiar part. What Snyder does is expand this story to incorporate additional facets that expand the mythology as well as the driving motivation for why Superman is so special. In this case, Snyder’s Krypton is populated by a society with designer DNA, where every person’s destiny is tightly controlled by predetermined genetic coding. Kal is the first natural-born Kryptonian in millennia, granting him genetic freedom, but making him a cultural abomination. However, Krypton’s own controlled population has failed it, and the planet is literally hours away from implosion as the film opens. Jor-El takes Krypton’s entire genetic history and encodes it into Kal’s cells, ensuring that once Krypton is destroyed, the basic knowledge to reconstruct its population is possible, should Kal survive and choose to rebuild Kryton’s legacy.

The entire Krypton opening is visually stunning and presents a scale and scope that dwarfs any previous iteration of Superman. And it establishes much more: General Zod (and his strained respect and conflict with Jor); the punishment of Zod and his followers; the benefits of sending Kal to Earth. And perhaps most importantly, Snyder’s gift for casting was immediately evident, as Russell Crowe’s Jor-El becomes one of Crowe’s best roles; and Michael Shannon’s excellent turn as General Zod still stands as one of the best comic book villains ever—both sympathetic and terrifying.

Man of Steel’s opening is the definition of huge, complex, bombastic filmmaking. It also does something important to set itself apart from the MCU: it establishes Snyder’s willingness to embrace a darker, more violent tone than anything the MCU has yet managed to this day. Without showing any graphic, bloody violence, Snyder still infuses his characters and the story with a grave seriousness that establishes real stakes through a willingness to let the good guys truly suffer and fail. Zod murders Jor-El; reluctantly, but with brutal efficiency. Zod’s banishment to the phantom zone is clearly a fate awful enough that even he is terrified. Lara is killed in the apocalyptic inferno of Krypton’s implosion. The MCU has certainly embraced tragedy and loss, but it is almost always surrounded by humor, heroic triumphs, and a careful balance of tone that the Disney Corporation will tolerate. Snyder pushed the envelope with Man of Steel’s opening sequence and did not let up.

Following the Krypton sequence, MoS continues to tell a familiar story of Superman’s origins, but Snyder shifts into a unique perspective: what would be the realistic, no-bullshit reaction of the people of planet Earth when they find out a race of superior aliens exists, and one of them is a refugee hiding on Earth? And what would life be like for this humanoid alien, as he slowly discovers the powers granted to him by Earth and its sun? If anyone contemplates these questions objectively, and particularly in light of what we have learned about humanity in a post-9/11 world (and, now more relevant, a post-COVID and post-Trump world), the reality is that mankind would aggressively reject the presence of an alien among them. And any being granted the powers that Superman develops would, statistically speaking, most likely, turn evil in light of their universal rejection by mankind, especially as the scale of their isolation is realized (see Brightburn for what happens without Jonathan and Martha Kent).

And THAT is what makes Snyder’s Man of Steel wholly unique and special. Filtering the entire movie through the lens of “how would mankind react to the emergence of an alien like Superman” establishes a realism and tone that utterly contrasts with virtually every non-comic book iteration of Superman.

The most prominent change to Superman’s conventional mythology that is a direct result of Snyder’s interpretation is the relationship between Clark Kent and his adopted father, Jonathan, played by the also excellent Kevin Costner. In basically every version I’ve ever seen prior, Ma and Pa Kent are morally flawless caretakers over a son they know will one day be a hero to all mankind. Snyder’s Jonathan and Martha Kent are far more realistic in their portrayals: they are terrified of what the world will think of their son, and delay telling him his true origins as long as possible. And even then, Jonathan emphasizes that Clark might one day choose to be a hero, but that it might not be a good idea to expose himself to that level of visibility for a variety of reasons, not the least of which is the outright rejection by humanity. Again, Snyder’s objective observation is that just the religious and scientific ramifications of the arrival of a being like Superman are so radical, that fear is a natural and likely result. How could any parent bear to see their child persecuted in this way?!

This is all very heady material to lay on an audience, and it poses questions and moral conundrums that are rarely explored in superhero movies, particularly, I would claim, the MCU (which I will address later, I promise). To anyone looking for a fun, action-packed superhero movie, Snyder’s thought-provoking perspective is diametrically opposed to expectations.

Once Clark learns his true identity from a long-lost Kryptonian colonial ship (more expanded Snyder mythology), Superman emerges into the world and experiences the first moments of true understanding about his identity, heritage, and potential. His first flight is an emotional and literal release of the tension established by his two sets of parents and their contrasting hopes and dreams for Kal/Clark. As Superman take flight, he seems to find a way to reconcile the two conflicting parts of his life.

And it is mere hours after this first flight that Clark is tested in a way that no other superhero experiences on their “first day on the job”. General Zod and his followers, freed from the phantom zone by Krypton’s destruction, have found a way to locate Kal, supposing that he is in possession of Krypton’s codex: the genetic library of Krypton’s population. Believing it to be a physical object, they arrive to reclaim it from Superman and, without telling the pathetic humans already on the planet, use the codex and their terraforming technology to rebuild Krypton and its population.

Zod’s arrival also compels Superman to reveal himself to humanity, offering himself as a sacrifice to Zod in the hopes of sparing mankind any punitive action. Here again, Snyder takes a very realistic look at how these events would play out. Terrified to discover they are not alone in the universe, the political and military leaders of the United States quickly agree to Zod’s terms and hand over Superman with nary a blink, hoping that Zod will take himself and his problems away from Earth.

The middle act of the film involves Superman learning Zod’s true intentions, and with the help of the reporter who tracked him down (Lois Lane, duh), escapes Zod’s ship and returns to Earth to do whatever he can to protect his mother, Lois, his adopted planet and its population. It’s a staggering challenge for an alien that only just learned his true potential after years of rejection by a callous world. And it establishes Superman’s true choice, as he contemplates the ultimate freedom Jor-El and Lara granted him and the altruistic obligation he feels to use his abilities to defend his world and everything that he loves.

The entire third act of Man of Steel is a breathtaking series of action scenes, as Superman fights Zod and his followers in Smallville and then Metropolis. After he defeats some Kryptonian flunkies, Zod discovers that the codex is imprinted on Kal’s cells, requiring his body (dead or alive), and shifts his focus on destroying the planet with his world engine that will terraform Earth to match Krypton’s environment. The world engine begins destroying Metropolis, and Superman risks his life to destroy it, sending the world engien and all of Zod’s followers into the phantom zone. Finally squaring off with Zod himself, Superman, still only one day “on the job”, learns that fighting a lifetime combat veteran of Zod’s brutality racks a terrible toll on himself and Metrolpolis, which is partially leveled. In the final moments of the struggle, Superman realizes that he must kill Zod to stop him—an act that flies in the face of audience expectations of Superman but aligns very well with the objectively logical conclusion of an inexperienced Superman fighting a clearly superior warrior whose powers are literally strengthening by the minute. It is devastating to Superman, and probably meant to be a pivotal moment his development as a character (we’ll never know, as Snyder’s vision is likely lost forever).

In its closing scenes, Man of Steel shows Clark retaining the anonymity of his secret identity, while Superman is heralded as a hero who saved the planet.

What Works, Works REALLY Good

There are a lot of elements of MoS that work; most people acknowledge that there is brilliance to be found in the film. What varies is whether the whole is greater than the sum of its parts; or not.

Here are some of the facets of MoS that I think are powerful contributors to its success:

- Henry Cavill as Superman/Clark Kent – Snyder’s casting was incredible, as Cavill, relatively unknown, respected the role he was cast in, recognizing that the opportunity and responsibility of playing Superman. He not only got into incredible shape, perfectly embodying the look of Superman, but he seems, in real life, to embody the positive kindness that people often associate with Superman as a character. Cavill possesses something as a human being that transcends his acting ability and infuses the character with the qualities that the character demands. Some might simply say “Hey, that’s what acting is!”, but I am convinced that Snyder saw in Cavill the qualities that Superman possesses. And despite Snyder’s Superman being more serious and conflicted than previous iterations, there are moments of pure, unadulterated Superman in the performance.

- Amy Adams, one of the best actors working today (full stop), gives a great turn as Lois Lane, a role that has varied in quality tremendously. The previous cinematic version was Kate Boseworth’s in Superman Returns, which was awful in every way. Margot Kidder’s turn in the original Christopher Reeves’ films was iconic but dated in its social portrayal of women. My favorite version was Erica Durance’s take in Smallville, but Adams delivers a level of skill that elevates the movie. As she does with every film she appears in…

- Many other actors: Lawrence Fishbourne’s Perry White, Diane Lane’s Martha Kent, Antje Traue’s Faora-Ul, and Christopher Meloni’s Colonel Hardy are all standouts. Each one gives a performance that shows complete immersion in Snyder’s vision, and represents excellent casting on Snyder’s part.

- Hans Zimmer’s score is incredible, which is saying something. He has scored plenty of superhero movies, the Dark Knight films amongst the best. In fact, though I have long agreed that John Williams has created the most iconic movie themes in film history (Star Wars, Indiana Jones, Superman, Harry Potter, Jaws, etc.), I think that Zimmer accomplished the impossible with not only a better score than Williams, but a Superman theme that is just as recognizable. I love about 2-3 tracks on Williams’ Superman score, but I love all of Zimmer’s Man of Steel score. I attended a concert where Zimmer conducted a variety of film score pieces, including a medley of Man of Steel music; it was stunning. I love the score for Man of Steel.

- The visual effects for MoS are incredible. The scale and scope of the story is matched by the excellent visual effects. From Krypton to the battles of Smallville and Metropolis, the sheer power of the Kryptonians is breathtaking.

- I really love the overt addressing of classical Superman themes. For example, when Zod reveals himself to the entire population of Earth, Clark first seeks counsel from his mother and at church. I loved the scene of Clark praying for guidance and seeking religious advice, because it fascinates me the implications of a being like Superman coming to a world where hundreds of millions of Christians look to Jesus Christ as their Redeemer. Superman is almost always portrayed as an allegory for Christ, and Snyder frequently uses religious iconography to support these allegories. But to directly address the implied connection between the two was great. Clark is taught a lesson about faith and trust, which really reminds him of bedrock principles that have always guided Superman. To re-learn these values on the cusp of his first challenge reinforced the enduring relevance of Superman as the greatest superhero.

Yeah, there are a lot more things. I feel like Russell Crowe and Kevin Costner (two Robin Hoods, lol) both deserve an additional shout-out for being so terrific in their performances, which complement each other so well. I think my point is adequately made: there is SO much to appreciate about Man of Steel.

Which is not to say that it is perfect…

What Doesn’t Work, Isn’t Great, But Maybe Still OK?

Snyder’s time in the DCEU has been met with mixed reactions, to say the least. I think much of the criticism is poorly articulated, in part because I think that a film that challenges people’s ideas and expectations can be a powerful window into greater appreciation and enjoyment. But there are a few things that Snyder fumbles in Man of Steel that are also problematic in his later DCEU films, Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice and Justice League (maybe? since we haven’t really seen his version yet…)

First and foremost are moments of dialogue that are just…terrible. My least favorite scene in Man of Steel occurs at the very end, after Superman has killed Zod. General Swanwick, the military leader responsible for dealing with the alien invasion of all Kryptonians, confronts Superman after trying to track him with a drone. The purpose of the scene is clear: Superman emphasizes that it is a waste of time and resources to try and discover his hideout/identity. But the dialogue is dreadful. Swanwick’s “Are you effing kidding me?” is lame, as are most PG-13 attempts to work around the adult language censors of the MPAA. Then his aide talking about “I think he’s kinda hot.” Coming moments after the emotional toll of Superman killing Zod and staging a scene to convey that Superman must be trusted on faith seems like a solid idea. But the execution grates on me terribly. I would posit that Snyder could perhaps use someone to give some objective feedback on dialogue this terrible in the hopes of coming up with almost anything else. And coming at the tail end of the movie leaves a bit of a sour taste in the memory of some viewers—not what you want in a movie you hope people will revisit frequently.

The only other complaint that I hear frequently is that the final fight in Metropolis is too long and too destructive. I fundamentally disagree with this complaint, but I do not begrudge anyone for making it. One of my first viewings of the film was in the theater with a friend who had been in NYC on 9/11, and the protracted fight that destroyed building after building was, in her words, “wanton and gratuitous destruction” and unnecessary. In her case, I understood the feeling, since she had untreated PTSD related to her experience in NYC.

My counter argument is rooted in the overall perspective of Snyder’s entire vision: a grudge match between two entities as powerful as Superman and Zod would undoubtedly lead to at least as much destruction as we see in the film, if not more. And to me, this scene also stood in stark contrast to much of the MCU, which rarely shows the implications of the catastrophic destruction superheroes wreak on the populace while fighting villains. The scale and scope of the destruction at the end of Man of Steel not only portrayed a believable level of destruction, but it is also the foundation of Snyder’s introduction of Bruce Wayne in Batman v Superman, which opens with a scene taking place concurrently to Superman’s fight in Metropolis, but from Wayne’s perspective on the ground, as he tries to get to his building in Metropolis to help his employees.

Taken in isolation, I understand objections to the extended length of the fight. But when the intentions of the opening of BvS are considered, the scene makes sense.

And that leads to my final concession about a flaw in Snyder’s DCEU plans, which began with MoS. Today, in the weeks before Zack Snyder’s Justice League is released on HBO Max, there is ample evidence that Snyder definitely had a very clear vision for his 5-film arc, and both MoS and BvS are exactly the way he wanted them to launch this arc. But too much of his plans were unknown in 2013, or even 2016 when BvS was released. Instead, audiences were given an admittedly grim version of Superman, a superhero that is universally known for being a beacon of positivity, sacrifice, and…well, heroism idealized. Snyder, DC, and WB failed to share with audiences the full vision, which Snyder has clearly indicated were meant to bring Superman eventually in line with traditional portrayals. His Superman had a true character arc over five films, and the first two were only the stepping off point for this arc. I think everyone involved failed to give enough of a glimpse of this vision to get fans on board to make the films successful enough to keep Snyder’s vision intact. There were mountains of other factors that eventually stalled the DCEU’s initial intentions, but too much secrecy is one of the biggest.

Let’s Wrap This Up…We’re Almost Longer Than The Film

I tend to let people’s criticism of Man of Steel, Snyder, and the DCEU go without engaging in any fights. It is important to respect other people’s opinions, and the number of people that come out swinging against all three is large enough that fighting the tide is useless. But I will say this: Every time I watch Man of Steel, I enjoy and appreciate it more, particularly Cavill’s Superman.

Releasing in the shadow of the MCU juggernaut just as it was picking up steam was tough enough. I really like Snyder’s vision for the DC characters, and I appreciate the gravitas and real-world consideration that he put into his films, which I consider universally superior to much of the MCU’s simplified world building. The MCU focuses largely on the heroes and ignores any realistic portrayal of how their heroes would impact a world even remotely similar to our own.

Man of Steel has many ardent defenders, and I hope that given time and distance, even more people will re-watch and re-evaluate it as a great film, not just a superhero flick. There is perhaps no better, more realistic melding of the superhero genre with the alien-invasion genre. In the aftermath of Nolan’s Dark Knight trilogy, I have said many times that I’m happy with whatever people do in future Batman movies, because I will always have that trilogy of near-perfect Batman films. It’s the same with Man of Steel: whatever DC does with Superman in the future can be good or bad; I won’t be overwrought. I will always have Man of Steel to watch as a nearly perfect Superman film.

Analysis by Jim Washburn

No Comments